PROVENCE, France, Aug. 11 (合众国际社;UPI)核武器对战争来说是最强大的工具,而一组新数据的观点表明,长期效应(后果)并不是如假设那样可怕。

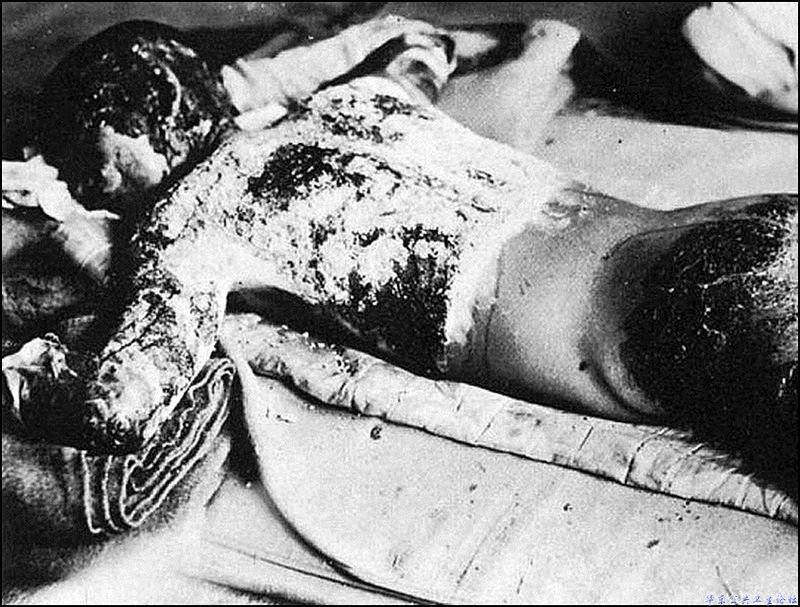

1945年美国在日本引爆了两枚核武器促使二次世界大战结束,一枚铀弹在广岛上空600米爆炸,另一枚钚弹在长崎上空500米爆炸。爆炸所产生的极端热量和强大的伽玛辐射及冲击波,致使爆心的1.5公里内的生物被高温和辐射立即被杀死,随着严重烧伤和急性放射病造成的死亡越来越多。法国的埃克斯-马赛大学的研究人员认为,虽在广岛和长崎核爆炸所造成的巨大的死亡和破坏,但对他们及孩子的健康影响长期以来一直怀疑。

之后人们估计幸存者和他们的孩子的癌症和基因突变是很严重。由法国大学的分子生物学家Bertrand Jordan, 对数据的长期研究分析表明并不是这样。

Bertrand Jordan 说“许多科学家印象中认为,幸存者将面临健康问题和非常高的癌症发病率及他们的孩子有很高的遗传性疾病”这与实际情况存在一个巨大差距。

研究者分析了辐射效应研究基金会(Radiation Effects Research Foundation;RERF)收集的数据。这是由日本和美国政府的共同努力的工作,跟踪调查核爆下100000个幸存者,20000儿童和77000个未暴露辐射的对照组数据。总的来说,幸存者的平均寿命只有减少了几个月的时间。这项研究发表在遗传学杂志上。

RERF,(源自杜鲁门总统在1947年原子弹受害者委员会)报道,幸存者中癌症相对风险与幸存者处于爆炸点的地址,年龄和性别有关系,距爆心越近健康风险越高,越年轻终生健康风险越高, 暴露于同样高辐射水平的女性要比男性风险高。

RERF报道,虽然幸存者中固体癌症发病率约10%,但大多数的幸存者没有患癌症。幸存者如果暴露于更高剂量的辐射,这个量比目前的安全限制高约1000倍,那患癌症的风险就增加了44%。考虑到所有的死亡原因,幸存者暴露于这种高剂量的辐射的平均寿命可减少了1.3年。

Jordan说:对于幸存的孩子健康或突变率的风险,虽然它是可能的,但没有显著差异,表明风险似乎是非常小。

研究人员说“该研究不是希望减少使用核武器的风险或者它在过去的毁灭性影响”

Jordan在研究中写道“广岛和长崎的核爆对长期健康影响的实际数据与人们的估计假设的差距巨大”。“这种扭曲部分一定来源于这样一个事实:辐射对人类仍然是一种新的和不熟悉的东西,其性质和作用方式是神秘的”。

他还强调,这项研究的结论“重要的是尝试澄清这些问题,并广泛传播科学数据,当出现这些问题时,可给出一个平衡的论点和更理性的决策。”

广岛

长崎

PROVENCE, France, Aug. 11 (UPI) -- There is no question that nuclear weapons are the most powerful of the explosive tools of war, but a new review of data suggests the long-term fallout from their use is not nearly as horrific as assumed.

Researchers at Aix-Marseille University in France suggest that for all the death and destruction caused by the detonation of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, health effects were not felt for many who were there or for their children, as has long been suspected.

The United States detonated two nuclear devices over Japan toward the end of World War II -- a uranium-based bomb exploded 600 meters above Hiroshima and a plutonium-based bomb was exploded 500 meters above Nagasaki. In both cases, the bombs generated extreme heat and a pressure blast with a strong burst of gamma radiation.

People exposed to the heat and radiation within 1.5 kilometers of the center of the blast were killed instantly, with more dying in the days immediately following as a result of severe burns and acute radiation.

Estimates and assumptions suggest cancer and genetic mutation, in survivors and their children, was rampant, but an examination of long-term study data by Bertrand Jordan, a molecular biologist at Aix-Marseille University, suggests this has not been the case.

"Most people, including many scientists, are under the impression that the survivors faced debilitating health effects and very high rates of cancer, and that their children had high rates of genetic disease," Jordan said in a press release. "There's an enormous gap between that belief and what has actually been found by researchers."

For the study, published in the journal Genetics, Jordan analyzed data collected by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, a joint effort by the Japanese and United States governments, which has followed 100,000 survivors of the bombings, 77,000 of their children and 20,000 not exposed to radiation as a comparison group.

Overall, survivors' average lifespan was reduced by only a few months.

The RERF, originally created by President Harry Truman in 1947 as the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, reports that relative risk for cancer among survivors is linked to proximity to the detonation site, age and sex -- the closer during detonation the greater health risk, the younger the person the higher the lifetime risk, and a higher risk for women exposed to high rates of radiation than for men.

Most survivors, the RERF reports, did not develop cancer, though incidence of solid cancer was about 10 percent higher among survivors. Survivors who were exposed to higher doses of radiation, about 1,000 times higher than current safety limits, had a 44 percent higher risk of cancer. With all causes of death considered, the average lifespan of survivors exposed to this higher dose of radiation was reduced by 1.3 years.

And while it is possible, no differences in health or mutation rates have been found among the children of survivors, which Jordan said suggests the risk for appears to be very small.

While the researcher does not want to minimize the risk of using nuclear weapons, or their devastating effects in the past, he said accuracy on the effects of the bombs matters.

"This contradiction between the perceived long-term health effects of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs and the actual data are extremely striking," Jordan writes in the study. "Part of this distortion must stem from the fact that radiation is a new and unfamiliar danger in the history of mankind, an agent that is unseen and unfelt, whose nature and mode of action are mysterious."

He also emphasizes, in the conclusion of the study, that "it is important to try to clear up these questions, and to disseminate widely the scientific data when they exist, in order to allow for a balanced debate and more rational decisions."